On Transcribing and Translating Spanish Paleography

One of the fun challenges of my archival work is having to engage with Spanish paleography—that is, early-modern Spanish handwriting. Even with formal training, any scholar in my field will tell you that certain scripts require extra time and patience to be able to decipher them. But with enough caffeine and determination, one can get through most documents, seeing them as puzzles to solve or codes to crack.

Yet reading through these documents and selecting the relevant ones for one’s given project are only the first steps of conducting research. This kind of evidence—raw data, if you will—needs to be processed and packaged. Unlike including a quotation from a secondary source or uploading an image of a painting, quoting from a sixteenth- or seventeenth-century document requires several steps.

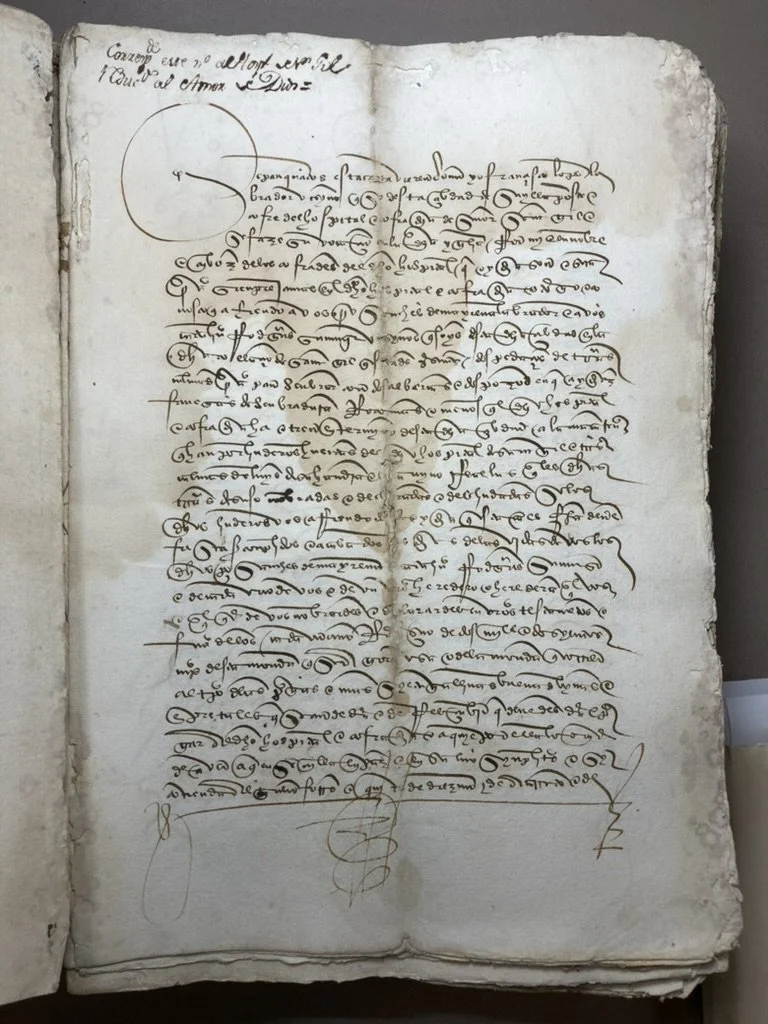

To illustrate, consider this late-sixteenth-century folio (courtesy of the Archivo de la Diputación Provincial de Sevilla). For the purposes of this post, let’s take just the first four lines. The first step is to transcribe it, word for word. Seems straightforward, right?

1. Transcription

Sepan quantos eſta carta vieren como yo françiſco lops la

brador visyno q so deſta çibdad de sivylla põſte e

cofre del hoſpital e cofradia de siñor sant gil e

se faze su vocaçiõ en la dha ygla . . .

The challenge one immediately runs into is that the above features spelling, syntax, punctuation, capitalization, and abbreviation from over 400 years ago—before any kind of standardization. So even a native Spanish speaker would likely struggle to understand every word. The next step, therefore, is to modernize the language into something more familiar in Spanish:

2. Modernization

Sepan cuantos esta carta vieren como yo, Francisco López,

labrador [y] vezino que soy de esta ciudad de Sevilla, prioste y

cofrade del hospital y cofradía de señor San Gil, y

[donde] se hace su vocación en la dicha iglesia . . .

Finally, one can now translate this phrase into English:

3. Translation

To those who may see this letter: I, Francisco López,

laborer [and] resident of this city of Seville, steward and

brother of the hospital and brotherhood of lord San Gil, and

[where] its vocation is done in the said church . . .

And voilà. Now we have something we can quote. Well, this kind of formulaic and fluffy opening is the kind of thing scholars know to skip in order to get to the actually quotable material, but the point here is to show the process by which it’s done.

One final point here: Learning how to decode Spanish paleography is an excellent skill if one needs to grade exams that are hastily written by students under a time crunch.